rance, the country with centuries of heritage, history, culture, cuisine and fine art is Europe’s oldest and largest nation; as well as a prime tourist destination. The country located in western Europe is the fourth richest country in the world.

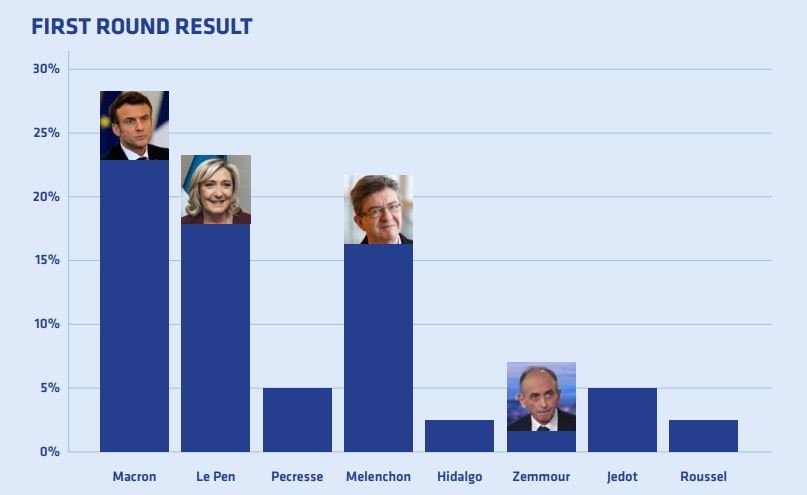

France’s politics are conducted within the framework of a quasi-presidential structure established under the Constitution de la Ve République (Constitution of the Fifth Republic) of France. The country refers to itself as a “integral, liberal, democratic, and communal parliamentary administration”. The constitution establishes the separation of powers and declares France’s ‘commitment to the Rights of Man and the foundations of national sovereignty as stated in the Declaration of 1789’. France is a unified country. In 2020, the Economist Intelligence Unit dubbed France a ‘flawed democracy’. The French presidential election of 2022 took place between April 10th and 24th in 2022. Because no candidate received a majority in the first round, a runoff election was held, in which Emmanuel Macron beat Marine Le Pen and was re-elected as President of France. Macron, who won the 2017 presidential election and whose first term runs through May 13, 2022, announced his intention to compete for re-election on March 3, 2022. After overcoming Le Pen, the leader of the National Rally, in the first round, he faced her again in the second round. The story behind this victory opens up some crucial factors that need to be more analyzed.

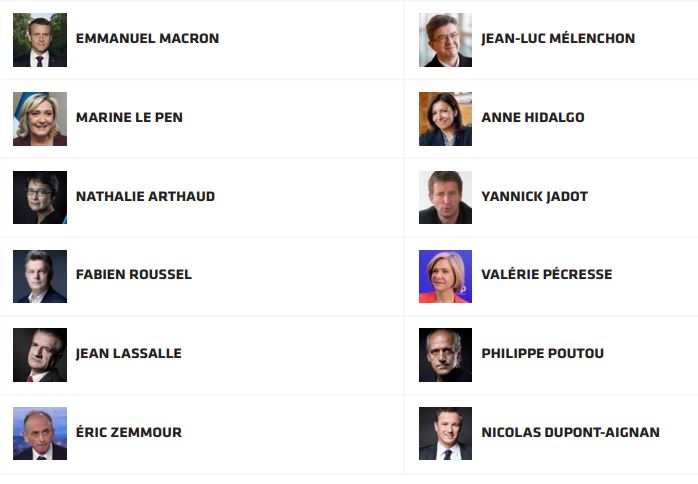

CANDIDATES’ FOR THE 2022 FRENCH PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION

The names of the 12 candidates who acquired 500 legitimate sponsorships were announced by the Constitutional Council on March 7, 2022, with the order selected by a lottery.

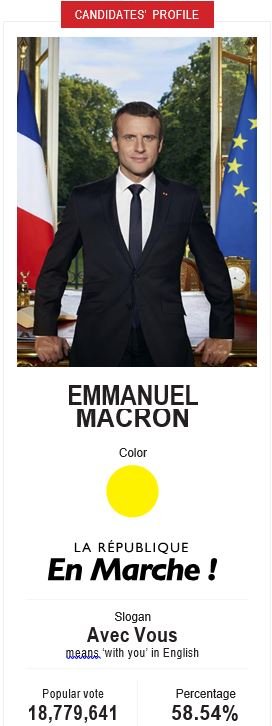

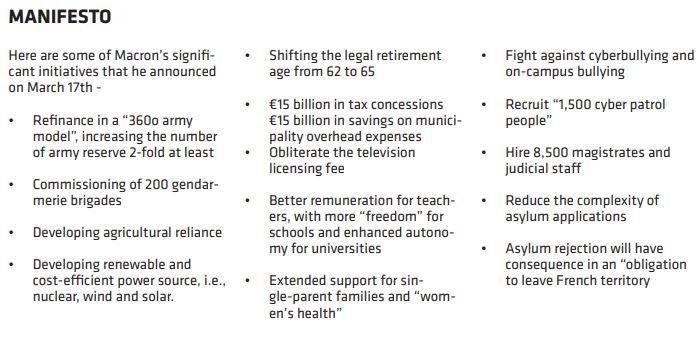

Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Macron’s party, which was renamed La Ré- publique En Marche (LREM) after the 2017 French parliamentary election, won a majority in the National Assembly the following month. In the 2022 presidential election, Macron defeated Le Pen for a second term, becoming the first French presidential candidate to win reelection since 2002.

During his presidency, Macron has overseen several re- forms to labor laws, taxation and pensions, and pursued a renewable energy transition. In 2018 yellow vest pro- tests and other rallies culminated in opposition to his domestic measures, notably a proposed gasoline tax. He has been in charge of France’s continuing COVID-19 pandemic response and vaccine deployment since 2020. In international policy, he lobbied for European Union changes and negotiated bilateral treaties with Italy and Germany. He also supervised a conflict with Australia and the US over the AUKUS security treaty, as well as French engagement in the Syrian civil war and participation in the international reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

CAMPAIGNING STRATEGY

First-round

Following the 2017 presidential election, the Republicans (LR) sent a questionnaire to its members on the topic of the party’s “re-foundation,” and Macron has undertaken a diplomatic strategy game, announcing his candidacy on March 3 in a “Letter to the French” and having fewer than 40 days to retain the French voters on his wing. Because of the Ukraine issue, Putin has refused to participate in campaigns, despite the fact that he needs more citizens’ support to succeed.

Macron told the broadcaster that “no one would understand at a moment when there’s war” if he was out electioneering “when decisions have to be made for our countrymen”. “I wish I could get to grips, start fighting, make contact with electors”. However, the president’s majority party was having trouble running campaigns into the same fundamentals.” During his brief candidacy, Macron has assumed a variety of roles in combating his dissenters on a national level: French President, President of EU, commander-in-chief of the army in battle, and electoral contender.

Second-round

Emmanuel Macron’s second-round campaign strategy is a far cry from his first-round campaign strategy, which pitted him against far-right rival Marine Le Pen. Macron went to comparable rough terrain to talk to enraged voters in order to get more votes. Macron is eager to be palpable “near to the people” after remaining distant for months while his competitors campaigned for the first round. Around 100 cultural leaders signed an opinion piece urging supporters to vote for Macron in the second round on April 24, stating that voting for Le Pen will only aid her cause.

Macron had to persuade supporters to vote for him again despite a mixed record on internal issues, including as his handling of the yellow vest riots and the Covid-19 outbreak. Macron spoke to his supporters, saying that the dissatisfaction of those who voted for Le Pen and those who abstained must be addressed. “I am no longer a candidate for a camp, but the president of all,” he declared, assuring that “none would be forgotten.”

Victory Analysis

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, Mr. Macron’s popularity skyrocketed as he attempted to engage diplomatically with both Kyiv and Moscow in the hopes of achieving peace. Mr. Macron said his far-right nationalist opponent relied on “fears and resentment” just days before the election, admitting that she was relying on his shortcomings in her campaign to succeed him. “She has managed to draw on some of the things we didn’t manage to do, on some of the things I didn’t manage to do to pacify some of the anger, respond quickly to what voters want, and in particular show herself as offering security to the middle and working classes in France,” the incumbent president said.

Mr. Macron declined to debate his opponents before the first round of this election, and he has barely campaigned himself. On the evening of April 20, however, Mr. Macron and Ms. Le Pen staged a discussion. Mr. Macron’s policies include lowering unemployment, which is presently at 7.4%, limiting access to some unemployment benefits, and raising the retirement age to 65, which has historically been difficult in France to achieve.

Voter Apathy

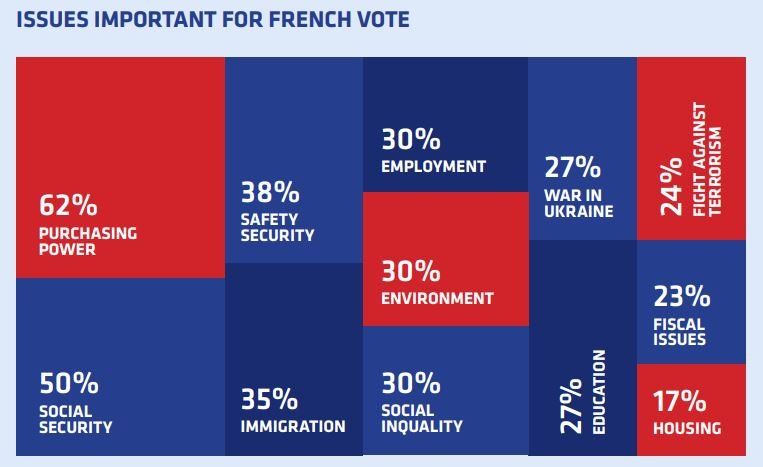

The 2022 campaign took place against the backdrop of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a cost-of-living crisis in France, a surge in far-left support among younger generations, and reports of widespread voter indifference. Macron, 44, benefited from his stance and diplomatic attempts toward the Russia-Ukraine conflict at the outset of his campaign. However, in the days leading up to the first round of voting on April 10, this support faded as French residents focused more on local issues and rising inflation.

Marine Le Pen, who has already stood for President of France three times, has chosen to focus on the economic hardships of French voters rather than her earlier rhetoric on the European Union and euro integration.

Putin links

Nonetheless, as the second round of voting approached, the two candidates and their proposals came under further scrutiny. Macron attacked Le Pen’s historical links with Russia and President Vladimir Putin in a two-hour television discussion on Wednesday, accusing her of be- ing reliant on Moscow. Macron, on the other hand, claimed that Le Pen’s intentions to make it illegal for Muslim women to wear headscarves in public would lead to a “civil war.” Macron’s new vision aims to keep his reformist program on track, with the president recently committing to help France achieve full employment and raise the retirement age from 62 to 65. Macron’s re- sounding victory is likely to calm French markets.

Social Networking Platforms Influence French Presidential Election Campaigns

The French presidential campaign is taking place on social media more than ever before. YouTube documentaries, Twitch live-streamed meetings, a few Instagram dancing moves, or a Tiktok bowling strike that has been viewed over 6 million times. These are perfect locations for swaying voters at a cheap cost

and with no time constraints. Emmanuel Macron, Eric Zemmour, and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who is leading the race thanks to a social media campaign, are the three contenders who stand out. Le Pen, on the other hand, was less concerned with the social media campaign approach. Strict media laws for posting campaign advertising remained in place, with fines for parties that allow un- lawful posters or video clips, and all presidential candidates were given equal space. It was difficult to use social media to promote more time campaigns.

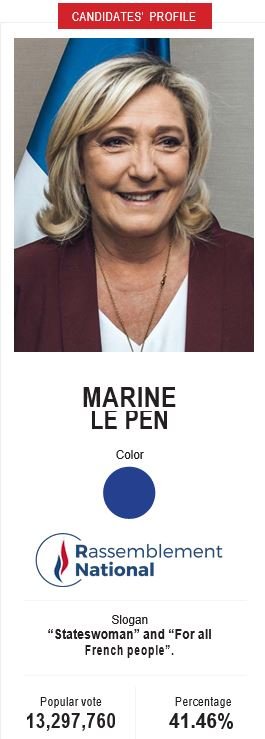

Marine Le Pen

Marine Le Pen, the president of the National Rally (RN), announced on 16 January 2020 that she would be run- ning in the election. She previously stood for president as the National Front’s candidate in the 2012 and 2017 presidential elections (FN). In the 2017 French legislative election, she was elected to the National Assembly. Le Pen grew up in the shadow of her father to become a national icon in her own right. Her popularity reflected the growing acceptability of the National Front as a legitimate alternative to France’s two main parties, and she continued to soften the party’s image. Marine Le Pen is running for the French presidency for the third time. She advanced to the second round this time but lost to Emmanuel Macron.

Since then, her party has gone through complicated periods and its policy of “de-demonization” of the Ras emblement National has left its scratch.

CAMPAIGNING STRATEGY

First-round

Unruffled by defections and the rise of a far-right challenger, Marine Le Pen has steadied her ship in the closing stretch of the French presidential campaign, moving ahead of opponents as she prepares for a rematch with Emmanuel Macron, whom she defeated in 2017. Marine Le Pen capitalized on a favorable comparison to her father’s excesses, portraying herself as calm, collected, open-minded, and less contentious. With one distinct advantage, she has learnt from her father the traps politicians must avoid if they are to widen their appeal: the gaffes, the wrong words, and the ill-advised utterances that permanently plague them and relegate them to the margins. On the campaign road, the National Rally leader has tempered her tone, avoiding controversy and put- ting a lid on the vitriol that previously marked her party. She has avoided talking about the “great replacement” without surrendering her anti-immigrant position.

It appears that the technique is working. Since January, the proportion of individuals who regard Le Pen as a threat has declined two points to 51%. While 50% of those polled stated they would “under no circumstances” vote for her, Zemmour (64%) and Mélenchon (64%) had greater numbers (53%). The onset of war in Ukraine, which upended a lackluster campaign and gave Macron a wartime lift in the polls, could easily have undermined Le Pen’s efforts to seem “presidential.” “Le Pen was

quick to blame Putin for the war, then quickly shifted the conversation to the war’s impact on people’s purchasing power, which has been her mantra since the be- ginning of the campaign,” said one observer. While con- demning Putin’s actions, the far-right leader slammed Western sanctions against Russia, citing their impact on French households already struggling with rising en- ergy costs. She has threatened to punish huge energy companies who profit “fatly” from the crisis, a position that is popular among her working-class supporters. Si- multaneously, she has reinforced her ideological creden- tials by threatening to reduce benefits to French citi- zens. Le Pen’s decision to avoid large rallies in favor of small-scale gatherings in towns and villages – both a tactical choice and a result of her party’s dire financial straits – has played into her hands, validating her deci- sion to shun large rallies in favor of small-scale gather- ings in towns and villages.

While her opponents fought on television and Macron focused on the world scene, the National Rally leader spent much of her time mixing with crowds in depressed neighborhoods, demonstrating her capacity to connect with everyday people. She has positioned herself as a “candidate of tangible answers,” laying out how she in-

tends to lower the cost of gasoline, gasoline, wheat, and other necessities. Her image is more focused than Ma- cron’s in the first round due to simultaneous rallies.

Second round

Marine Le Pen, the far-right contender, enters the sec- ond round of the presidential election against President Emmanuel Macron with a new billboard at the center of her campaign, emblazoned with the words “For all French people.” This is the most recent phase in her me- dia effort to “de-demonize” her political party. In post- ers, she presents herself as a normal person in an at- tempt to establish political credibility, which draws a telling parallel with her poster for her first meeting with Macron. Her team used slogans to transmit numerous messages in order to increase campaign interest.

“The society that Marine Le Pen wants is one of national preference, discrimination, xenophobia disguised as constitutional principles, a rejection of any form of vari- ety and hospitality,” culture and sports industry leaders said. As a result, her performance tends to deteriorate over time. Although Le Pen recognized the loss to Ma- cron in the runoff, she was quick to characterize the re- sult as “a success” for her party.

1. PENSIONS ARE A MAJOR SOURCE OF CONTENTION

The two finalists have certain economic viewpoints in common. Ms. Le Pen, on the other hand, differs from Mr. Macron on a few grounds. She proposed, for exam- ple, repealing the real estate wealth tax and replacing it with a new financial wealth tax. She recommended a 5.5 percent VAT reduction on energy. Mr. Macron proposed to triple a special purchasing power bonus that is tax- free and exempt from social security contributions, in- cluding welfare benefits (RSA, France’s employment benefit payment) and unemployment insurance.

Most notably, Ms. Le Pen was pushing for a legal mini- mum retirement age of 60 (for those who worked before the age of 20 and for at least 40 years), but Mr. Macron wanted to raise it from 62 to 65, which would undoubt- edly be a key point of contention between the two vot- ing rounds.

2. NUCLEAR POWER AGREEMENTS, WHY NOT RENEWABLE ENERGY AGREEMENTS

With the development of six new-generation power plants, Mr. Macron is arguing for the rebirth of the French nuclear sector. He also supports the develop- ment of solar and wind energy, as well as hydrogen (50 offshore wind farms by 2050). At the same time, he wants to impose a carbon tax at Europe’s borders and provide low-cost electric car rentals. Ms. Le Pen is a sup- porter of nuclear power as well. Several independent or- ganizations have criticized both candidates for flaws in their environmental proposals. “The legitimacy of Ms. Le Pen’s suggested plan” on the environmental transi- tion, according to The Shift Project. Mr. Macron, on the other hand, responded too late for them to examine his program. In their study of the two candidates’ environ- mental proposals, the Climate Action Network cast doubt on their pledges.

3. PERMANENT DISCUSSION VS. REFEREN- DUM POLICY

Ms. Le Pen’s planned institutional reforms are a perma- nent aspect of her Ras emblement National (RN) par- ty’s electoral platform. The use of referendums to allow the people decide on particular matters, whether the referendum is initiated by the government or citizens, is at the top of the list. The far-right candidate also want- ed to revert to a non-renewable seven-year presidential term and introduce proportional representation.

Mr. Macron, on the other hand, is not a big fan of ref- erendums and has avoided them throughout his five- year presidency. However, since the Yellow Vests crisis, he has been persuaded to the value of public debate. During his campaign, the outgoing president declared frequently that he wants more citizen participation in political decision-making, including a “permanent” great national debate on key issues.

4. A CLEAR DIVERGENCE IN EUROPE

Mr. Macron has positioned himself as an outspoken pro-European contender in 2022. He intends to ensure Europe’s energy independence, as well as increase the skills and coordination of European militaries. Ms. Le Pen no longer calls for the EU to be dismantled or the euro to be abandoned. Officially, she demands that these treaties be renegotiated. However, she main- tains that she wants to make French laws superior to European rules, even if it means France being kicked out of the EU.

5. FOREIGN POLICY IS ANOTHER CONTENTIOUS SUBJECT

Both Mr. Macron and Ms. Le Pen stated that France would not become a co-belligerent in the conflict. How- ever, while the current president has been a leading force for the implementation of sanctions against Rus- sia, the RN leader believes that these penalties are threatening French purchasing power. Ms. Le Pen, whose party owes a Russian creditor money, goes even farther in her manifesto, suggesting an “alliance with Russia on key fundamental matters” like European se- curity. Both second-round contenders are aware that the Kremlin does not want Ukraine to join NATO. But, unlike the incumbent president, Ms. Le Pen is calling for France to leave NATO’s integrated military command system once the war in Ukraine is finished, citing inde- pendence and military sovereignty as reasons. The pres- idential candidates also disagree on free trade agree- ments.

6. ON IMMIGRATION, MARINE LE PEN WAS FAR MORE EXTREME

When it comes to limiting the right to asylum, Mr. Ma- cron and Ms. Le Pen are on the same page. Similarly, both candidates support restricting access to French na- tionality, though to varying degrees.

Mr. Macron wants to condition it on mastery of the French language, but his opponent wants to abolish birthright citizenship and easy nationality gain through marriage. She also plans to alter the Constitution to add scenarios that could result in nationality being revoked.

7. ON SOCIETAL CONCERNS, THE DISPARITY IS LESS PRONOUNCED

Mr. Macron wants to raise teachers’ compensation in ex- change for new responsibilities, whereas Ms. Le Pen wants to give them a 3% annual raise and limit the number of students per class to 20 in primary school and 30 in high school. Mr. Macron plans to reinstate mathematics into the main high school curriculum, re- structure vocational certifications, and boost appren- ticeships in the field of education.

During Mr. Macron’s five-year presidency, he made med- ically assisted reproduction available to all women, over Ms. Le Pen’s opposition. Although the RN candidate no longer favors repealing marriage for same-sex couples, as he did in 2017, the introduction of the citizen-initiat- ed referendum could reignite some of these concerns. Mr. Macron, who has declared gender equality his “top goal for the next five years,” intends to incorporate a

professional equality index, with financial penalties for unequal businesses. Ms. Le Pen, who just recently reaf- firmed her support for the 2000 equality law after years of opposition, did not campaign on these themes.

Candidates have made their opposition to radical Islam a point of emphasis. Mr. Macron plans to combat “sepa- ratism” by rigorously regulating foreign religious money. The RN’s president goes even farther, calling for a ban on wearing the veil in public and in university settings. During the campaign, this caused a stir among Muslims.

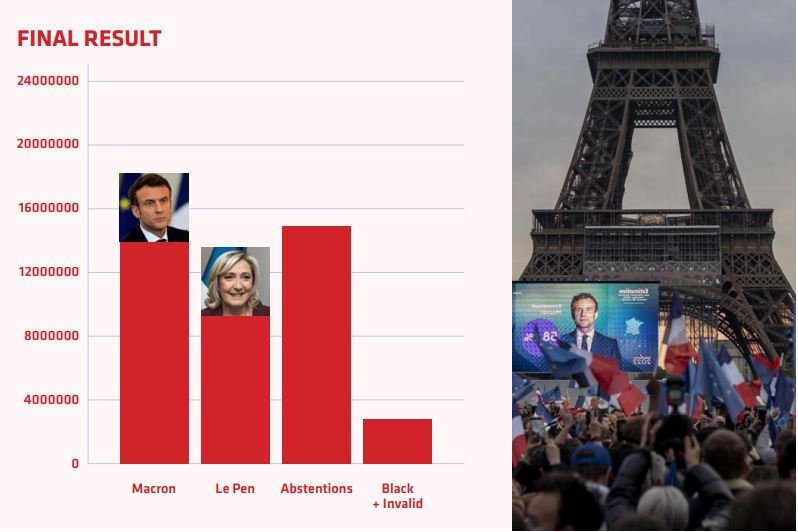

In the second and final round of voting, the centrist Ma- cron of the La République En Marche party is expected to gain roughly 59 percent, with Marine Le Pen of the nationalist and far-right National Rally party on 41 per- cent. She declared her outcome a “success” for her po- litical movement following the exit polls. “The French expressed a desire for a strong counterweight to Emma- nuel Macron this evening, for an opposition that would continue to defend and protect them,” she said.

Macron has maintained a considerable advantage over his closest challengers and has played a political long game in order to win re-election. When the news was announced, Macron’s supporters gathered on the Champs de Mars in central Paris, in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, erupted in applause. The party was much more low-key than it had been after Macron’s triumph in 2017, though he did walk to deliver his address to the European hymn, also known as the “Ode to Joy.” Macron promised to be “president for every one of you” in his victory address. He then thanked his supporters, ac- knowledging that many of them voted for him solely to keep the extreme right out, as they did in 2017. Macron

stated that his second term will not be a repeat of his first, and he pledged to solve all of France’s current is- sues. He also spoke directly to Le Pen supporters, stat- ing that as president, he must find a solution to “the rage and conflicts” that drove them to vote for the far- right.

It will be my responsibility and that of those who surround me

– Macron